Blast from the Past: The Issue of "Riots" in Hong Kong

- Dan

- Jun 25, 2019

- 3 min read

Updated: Aug 6, 2019

In recent weeks, Hong Kong has seen its largest and most violent demonstrations for a generation, triggered by Carrie Lam's controversial extradition bill. For the city government and official mainland Chinese media, the worst of these events were described as "riots", a crime punishable by up to ten years in prison. The use of this term has angered protesters now asking for it to be formally retracted.

Without wanting to enter the debate over the definition of a riot and the extent to which recent demonstrations can be so considered, it is important to srutinize this loaded term and its selective use over time by different interest groups.[1] Upon closer inspection, the origins for the word's controversy can be found in a history that many observers may have forgotten or been unaware of.

Look back over half a century and the major news story coming out of Hong Kong seems like a case of déjà vu. In April 1966, anger over a decision to raise fares for the local ferry service escalated into a much wider display of civil disobedience. Protesters threw stones at police, looted shops and set fire to public facilities, leading to one death and well over a thousand arrests. The events marked the start of Hong Kong's long-held tradition of explosive civil activism.

The colony's newspaper of record, the South China Morning Post, described "Wild Riots in Kowloon" involving "thousands of beserk rioters". These were followed by "leftist rioting" the following year, when a small labour dispute erupted into a larger affair fought between local communist sympathisers and British security forces over many months. Curfews were enacted and over 50 people killed as a wave of bombings terrorised the city.

Major civil unrest in 1966, described as "riots" by Hong Kong's paper of record (SCMP).

By contrast, recent incidents in Hong Kong have been described by the SCMP and foreign press in relatively neutral terms like "protest", rather than "riot". Western media reports have largely failed to mention the events of 1966-67, if only to provide a sense of scale or historical context. Coverage has also neglected to mention that Hong Kong's current ten-year prison sentence for rioting – at the root of continued calls to retract the term's use – actually originated as a response by British administrators to the unrest of the late 60s.[2]

Is this neglect a symptom of colonial shame on behalf of Western (and especially British) news media? Or is it simply that such historical, pre-handover events are now seen as irrelevant to the current discussion? In any case, the apparent amnesia for the colonial era and one of its more draconian legacies seems to have been shared by some demonstrators in Hong Kong, many of whom have been spotted provocatively waving around Britain's national flag, the Union Jack.

A lady waves the Union Jack during June 2019 protests in Hong Kong (Héctor Retamal/AFP/Getty Images/The Guardian).

The Chinese media have also chosen to forget the protests of 1966-67, though for their own, slightly different reasons. Those years saw the start of the decade-long Cultural Revolution in China, another shame-ridden era and a topic that remains heavily censored on the mainland. The movement had great influence on contemporary Hong Kong activism, sections of which displayed Maoist slogans and waved Little Red Books.

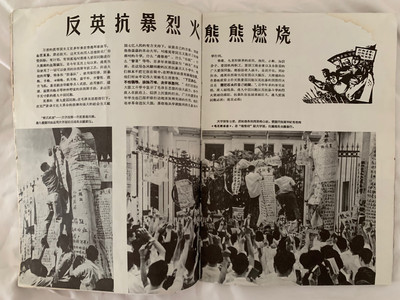

As seen in the below image, official mainland propaganda described those events in 1967 as 抗暴 ( kàngbào), meaning an uprising against violent repression or brutality. The term conveys a heroic, moral superiority over the chaos suggested by words like "disturbance" or "riot" – 骚乱 (sāoluàn) and 暴动 (bàodòng) in Chinese. It is precisely those latter descriptions that have been used by the police and government in Hong Kong on this occasion, causing anger among demonstrators and further stoking unrest.

A 1967 propaganda pamphlet from the mainland titled 'Uprising Against British Brutality'.

The Beijing government have echoed the Hong Kong authorities' verdict, foreign affairs spokesperson Geng Shuang recently referring to an "organized riot". But official commentary in China has so far been extremely restricted, and state media have focussed on blaming alleged "foreign interference" instead of pushing the "riots" narrative.[3] Rather than report on an estimated two million-strong march against the extradition bill, the China Daily covered a demonstration by a mere 100 people that same day, reported to be local parents protesting against US meddling.[4]

The controversy over the term "riots" may seem trivial, but it demonstrates the continued relevance of history in shaping how people think and talk about present-day events. This is especially true in Hong Kong, a place that continues to carry significant historical weight, both for its citizens and for the mainland Chinese government. For Carrie Lam's administration and its supporters in Beijing, reflecting on that history may be useful as they determine how to respond to the present crisis.

Notes:

[1] For an exploration of the riot definition, see this SCMP article.

[3] See this Global Times piece.

Comments